Let Trainspotting Teach Students

The perilous and timeless lessons of an iconic Scottish film are what’s missing from the SHS health curriculum

October 2, 2019

Parents, policy-makers, professors, and priests alike have long shared one burden: making crystal clear the detrimental effects of drug use. The critical nature of this responsibility can not be understated–in the next fifteen years, America is on track to lose over one million people to opioid addiction. Various officials have made their own proposals on how to combat this epidemic, and though I unconditionally support the demands for legal action and the efforts to destigmatize addiction, the purpose of this article is not to make those explanations. Rather, I want to talk about a film.

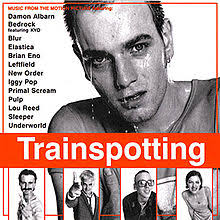

Danny Boyle’s 1996 feature film Trainspotting is the answer to the dilemma facing health educators across the nation: How do we decrease illegal and irresponsible drug use in America? In fact, this movie unequivocally proves there are absolutely no benefits to using drugs. (Caveat: Trainspotting can not reverse the trauma, chemistry, or deep misfortune that has perilously trapped so many people in the depths of addiction.)

In English classes, students are told to “show not tell.” Trainspotting very effectively shows. Rather than claiming to have the solutions to the aforementioned causes of addiction, Boyle directed a film that shows the causes of drug addiction in living, breathing color. To that end, the film is very simple–merely the story of man, his friends, and the needle.

Trainspotting is not a film that can be recommended on a whim–or without explanation. The movie is uncouth, dirty, and anxiety-inducing. No movie, however, has ever stuck with me in the way that Trainspotting has.

It’s simple, really: Have you ever met Indiana Jones? How about Rocky Balboa? Mary Poppins? I’m guessing not. However, the characters of Trainspotting–Renton, Begbie, Spud, Sick Boy, and Diane—you’ve met them. They’re the people who stand behind you in line at the grocery store, or the people having a loud conversation at the table next to you. They fix cars; they sell houses; they cook in restaurants; they fish the Atlantic. Trainspotting is not a movie the audience lives through–it’s a movie that truly lives within an audience. Trainspotting is depressingly realistic and completely unforgettable. The film’s gritty Anglo-allure pulls you in–its story repulses you. And then it’s over.

Why the predictable decay of a few fictional Scottish junkies remains so present in my mind, I can not answer. But their tragic, synaptic occupation has done for me what no health class ever could: prove–in no uncertain terms–the perils of drug use.

At Scituate High School, the responsibility of delivering the Trainspotting message falls to a team of health teachers. SHS health teacher Shana Lentini said her role is to demonstrate the detrimental effects of drugs on physical and mental health. She explained that as teenagers are exploring “what they want to do in life,” they need to know drugs and alcohol will not support them.

Trainspotting opens with a famous monologue delivered by protagonist Renton: “Choose your future. Choose life . . . But why would I want to do a thing like that? I chose not to choose life. I chose something else. And the reasons? There are no reasons. Who needs reasons when you’ve got heroin?”

Health educators want to make it clear that “something else” isn’t an option. And how do they go about doing that? According to Lentini, “open discussion” is the best approach. I agree.

During Black History Month 2019, Scituate High School students participated in formal and informal discussions about race and privilege. To address concerns about ignorance, and to hold the fleeting attention of an otherwise uninterested student body, the decision was made to show the movie The Hate U Give. The same principle needs to be applied to discussions about drug abuse.

While the effects of opiate abuse are likely more familiar to Scituate students than code-switching, gang violence, or police brutality, it is naive to assume that students understand the inimical nature of drugs beyond what they have been taught in health classes. Young people should not feel ashamed of this almost innocent lack of awareness. Teenagers have their whole lives in front of them, so why would they want to spend time earnestly thinking about the fastest ways to end what has yet to begin? And yet 12% of all heroin overdose deaths kill 15-24-year-olds.

A school-sanctioned viewing of Trainspotting would cast away any doubt in the minds of health teachers that their worksheets, their anecdotes, or their statistics were ineffective. What this movie takes from innocence it gives completely to understanding and caution. Conquering opiates begins with confronting them, and within the ethical and logistical confines of a high school environment, one option exists–showing students Trainspotting.