A Curriculum for Today

The Classes We Want (and Need) in a Changing World

March 29, 2021

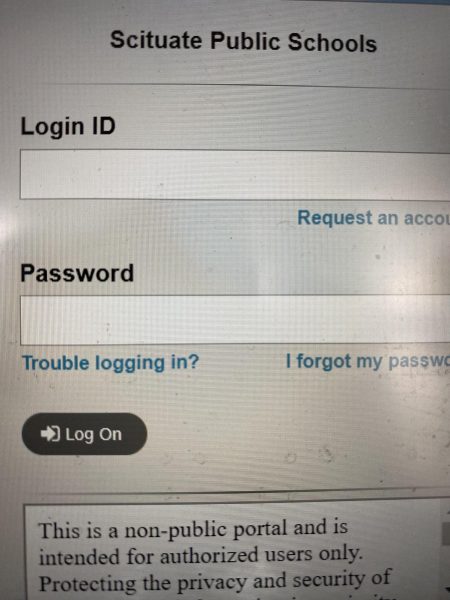

As April approaches and the 2020-21 academic year draws to a close, one of the decisions plaguing freshmen, sophomores, and juniors is course selection. Although it often begins as an enticing process, the freedom in one’s education can quickly become limited. In many students’ experiences, a broader curriculum with more unique and meaningful classes is a dream rather than a reality, and this leads to a lack of excitement when it comes to learning and choosing an educational path at the high school level.

“I think there’s too much repetition in the curriculum,” says SHS junior Henry Sherman, who says his options are somewhat limited when it comes to learning about areas he is passionate about.

With two years of U.S. History, three years of standardized English classes, and a rigid math curriculum, Scituate’s graduation requirements are reminiscent of traditional expectations regarding American high school education. However, these requirements have the power to change within a single school committee meeting, and, according to Social Studies Department Chair Steve Swett, this could be an important step toward creating a curriculum that reflects changing times. “It’s a question of evolving to stay relevant,” he says.

When considering changes to an established system of earning credit at a public high school, one can’t dismiss the common concerns that arise in these situations. “We work a lot to have history be engaging for students,” Swett explains. “Part of that is being able to connect history to where students are and what they’re familiar with.” In other words, students often relate to history they feel connected to, and American history (told primarily from a straight, white, male perspective) is a perfect example.

Another caveat to curriculum changes has to do with the one thing that has always been an anticatalyst for positive change: money. According to SHS English teacher Anne Blake, the English Department has been diligently working to include more senior selectives such as Women’s Literature and Diverse Voices in Literature, which provide an opportunity for increased variety in perspectives to encourage students’ compassion. “We had this all ready and raring to go, and enough people picked the classes this year in order for them to run, but we didn’t have the money to pay the teachers to actually put together the curriculum,” Blake explained. Money can be a hindrance when it comes to creating new classes, especially those that are added to the standard requirements. Sherman, Swett, and Blake all agree: the best way to create a curriculum for the moment is to either change the requirements or change what is taught within said requirements.

When considering this prospect, there is a good deal of flexibility and new opportunities that arise. For Sherman, this could involve an environmental science class at the Advanced Placement level, recreating one year of U.S. History to be focused on unheard and marginalized voices, or adding a year of World History to highlight African and Asian pre-colonial life. For Blake, this would consist of the current English classes being revamped to represent more varied and thought-provoking perspectives in literature. For Swett, this has a lot to do with implementing DEI in the context of race, class, and gender in existing courses.

In Sherman’s opinion, being a part of a “homogeneous community” such as Scituate makes reevaluating the curriculum all the more important, as it encourages empathy and awareness in a world that seems to be changing rapidly. Although learning about the American Revolution is close to home, both physically and figuratively, the topic is explored in nearly every other grade, and it enforces the white, traditional, westernized approach to education that reinforces the homogeneity of the bubble we have trapped ourselves in.

As Blake points out, “It’s so important that, as teachers, we are here to not just teach you how to read or how to write or how to think, but to also give you new opportunities to view the world in a different way.” If that goal is to be accomplished, the changing world that we find ourselves in must be accompanied by a changing curriculum to represent the moment. Then and only then will we be able to, in Swett’s words, “Have the most positive impact possible on our students during the time that they’re here.”